Everything’s better with bitterquelle…

by Ken Previtali

04 March 2015 (R•071415)

Reading the recent post on Hunyadi Janos reminded me of how the details of what we might consider commonplace can be intriguing. What could be more commonplace than water?

Translated from German, bitterquelle means “bitter spring.” Water containing sulfates of magnesium and sodium tastes slightly bitter, and thus Andreas Saxlehner named his Budapest water aptly.

In 1882, a New York City importer, P. Scherer & Co, published “A Complete List of Mineral Waters, Foreign and Domestic with Their Analysis, Uses, and Sources.”

It begins with:

“In presenting this list on mineral waters and products of mineral springs mentioned in this pamphlet, all of which are continually kept on hand by us, we beg leave to especially caution the profession that unless mineral waters are obtained fresh, no dependence is to be placed on their efficacy. We therefore have arranged with our correspondents to receive continual supplies by every steamer, and as it is a specialty of our house, and has been so for the last twenty years . . .”

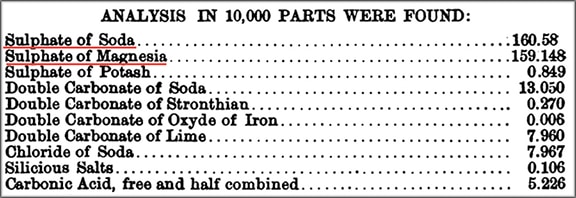

If you can believe them, the Scherer company kept on hand over 50 different “fresh” mineral waters from America and Europe, including the Hunyadi Janos Bitterquelle which they considered to be “one of the best and cheapest natural aperients.” They stated mineral analysis for Bitterquelle as:

According to current medical research water containing these minerals certainly makes digestion and the normal outcome of digestion much better for those with sluggish constitutions. So, at least one of the curative claims mineral water made by mineral water purveyors over the last 500 years or more was a good one.

But was everything better with “bitter” water? Mineral and spring water bottlers believed it, and so did their hundreds of thousands of customers. And why wouldn’t ginger ale be better if made with mineral or spring water? They believed that too, but let’s back up a bit.

What is mineral water and what is spring water? The US Food and Drug Administration sees it this way:

“Water containing not less than 250 parts per million (ppm) total dissolved solids, coming from a source tapped at one or more bore holes or springs, originating from a geologically and physically protected underground water source, may be “mineral water.” Mineral water shall be distinguished from other types of water by its constant level and relative proportions of minerals and trace elements at the point of emergence from the source. . . No minerals may be added to this water.”

And for spring water:

“Water derived from an underground formation from which water flows naturally to the surface of the earth may be “spring water.” Spring water shall be collected only at the spring or through a bore hole tapping the underground formation feeding the spring. There shall be a natural force causing the water to flow to the surface through a natural orifice.”

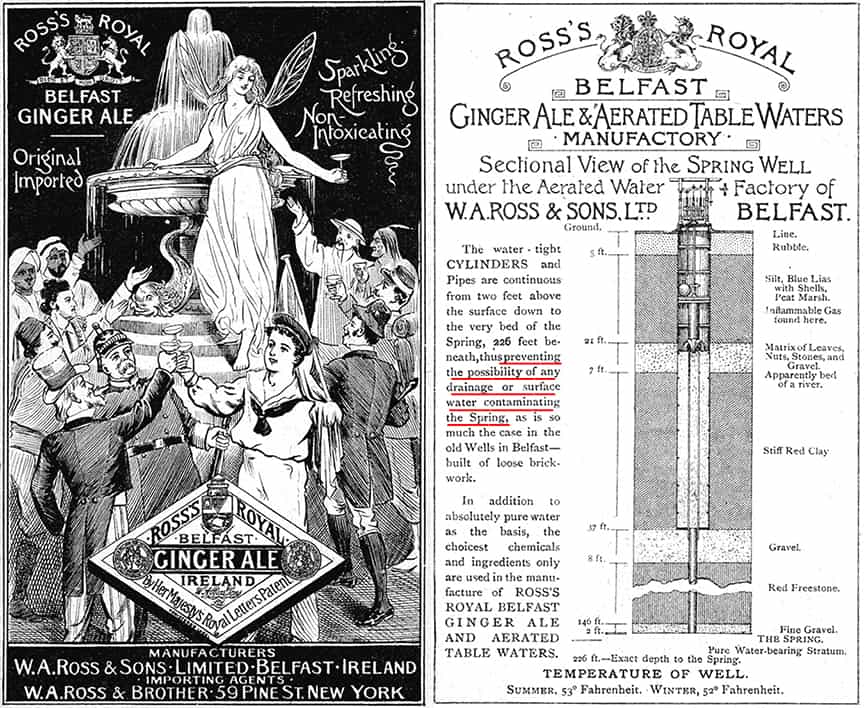

Ross’s Well – In the 1880s cholera and other water-borne diseases were rampant and the general public was correctly concerned with the purity of any water they drank. Bottlers went to great lengths (and depths) to assure their customers that their water was safe.

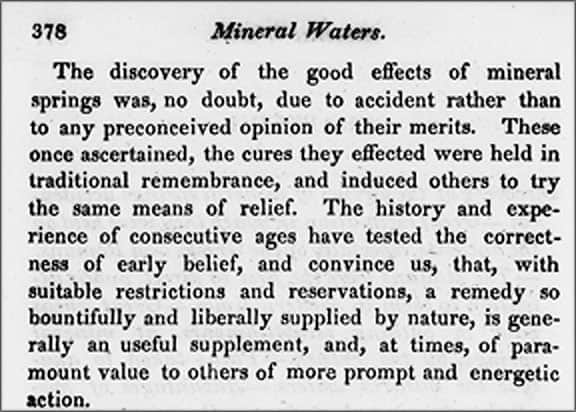

By today’s FDA definitions, it appears that the difference is what is in the water. However, what exactly was in mineral water was disputed mightily by chemists and physicians alike for at least three centuries. But let’s back up a bit again. The healing properties of waters have been touted and promoted since the ancient era. In his book, On Baths and Mineral Waters published in 1831, John Bell, M.D., writes:

Bell goes on to say “The Greeks, whose knowledge of medicine was greater than that of the nations who had been their precursors, paid honours to warm or thermal springs, as a benefaction by the Deity, and dedicated them to Hercules, the god of strength. They made use of them for drink, for bathing, and as topical remedies. Hippocrates tells us of warm springs impregnated with copper, silver, gold, sulphur, bitumen, and nitre; and forbids their use for common purposes.”

The dispute about the efficacy of mineral water as a healing agent began in earnest when in 1756 noted Irish physician Dr. Charles Lucas took issue with the prevailing beliefs on mineral water. Christopher Hamilin, professor of history at University of Notre Dame wrote that Dr. Lucas “had railed at the pretension and corruption of mineral water physicians and chemists in similar treatises on mineral waters. The ‘most pompous’ of the numerous tracts on mineral waters were written, Lucas noted, by men ‘living and practicing upon the spot, not always competent judges of the subject, but always interested in the fame of the particular water, which was their idol.’ “

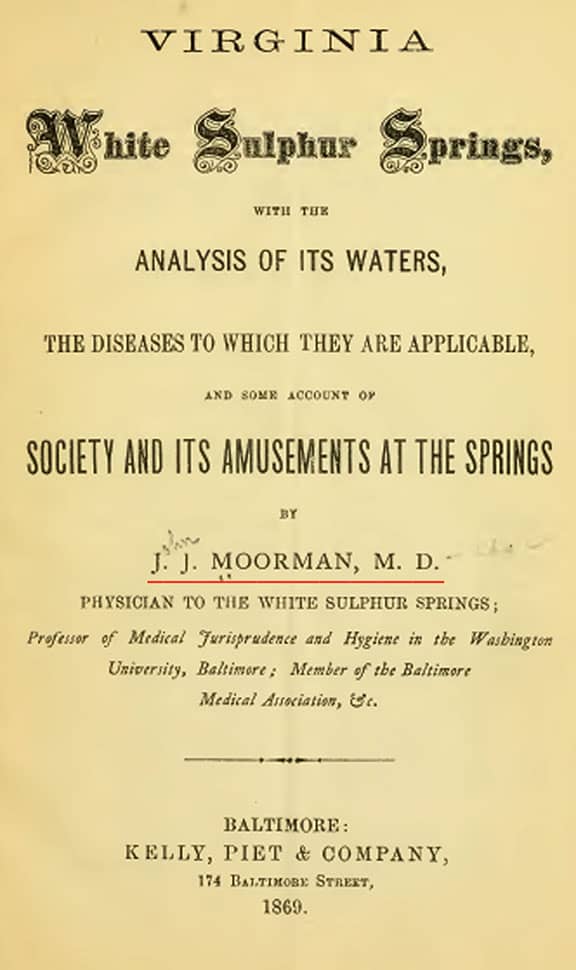

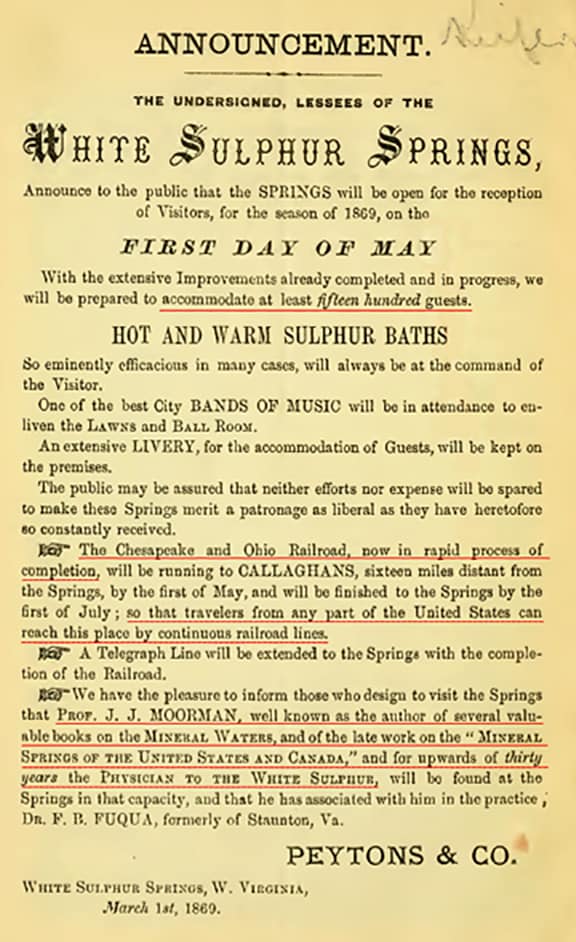

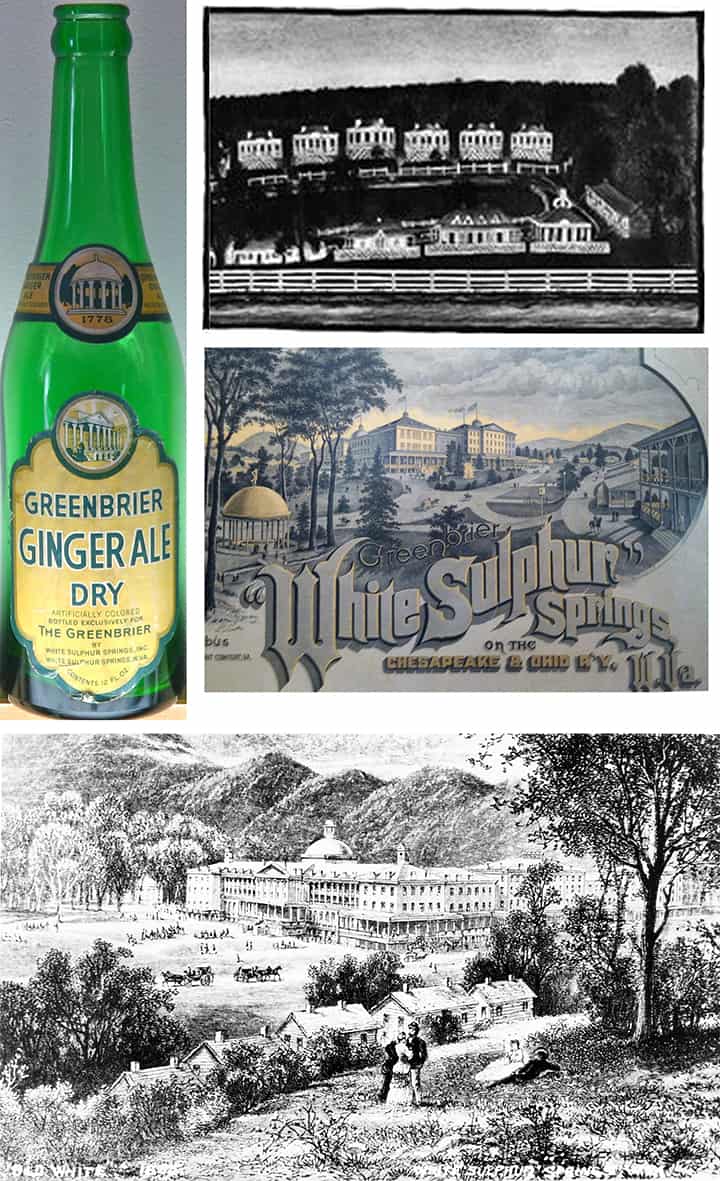

White Sulphur Springs cover – West Virginia’s White Sulphur Springs was one of the oldest and most famous in America. Established in 1778, it too had its “resident physician” treating the “invalids” who flocked to the spa during the “mineral water season.

Professor Hamlin continues that “while Lucas was willing to accept in principle the claim that mineral waters had medicinal potency, he felt that their use was completely devoid of legitimate medical rationale: physicians were viciously attacking one another all the while being ignorant of the properties of waters. At Bath [England] and elsewhere wealthy invalids were fleeced by mercenary physicians, yet they ignored the advice they paid for, insisting on taking the waters without regard to season or constitution. . . Ultimately the spas were nothing but gathering grounds for sycophants, Lucas concluded, and it was futile to wish otherwise. ‘Forms, fashions, and flattery rule the world,’ Lucas wrote, ‘and a man may as well refuse to eat modish stinking wild fowl or venison at a great man’s feast, be insensible to the beauty of his mistress, hound or horse, or disrelish any other prevailing vice or folly, as [rather than] decline drinking of his favourite spring, or deny having received benefit of it.’ “

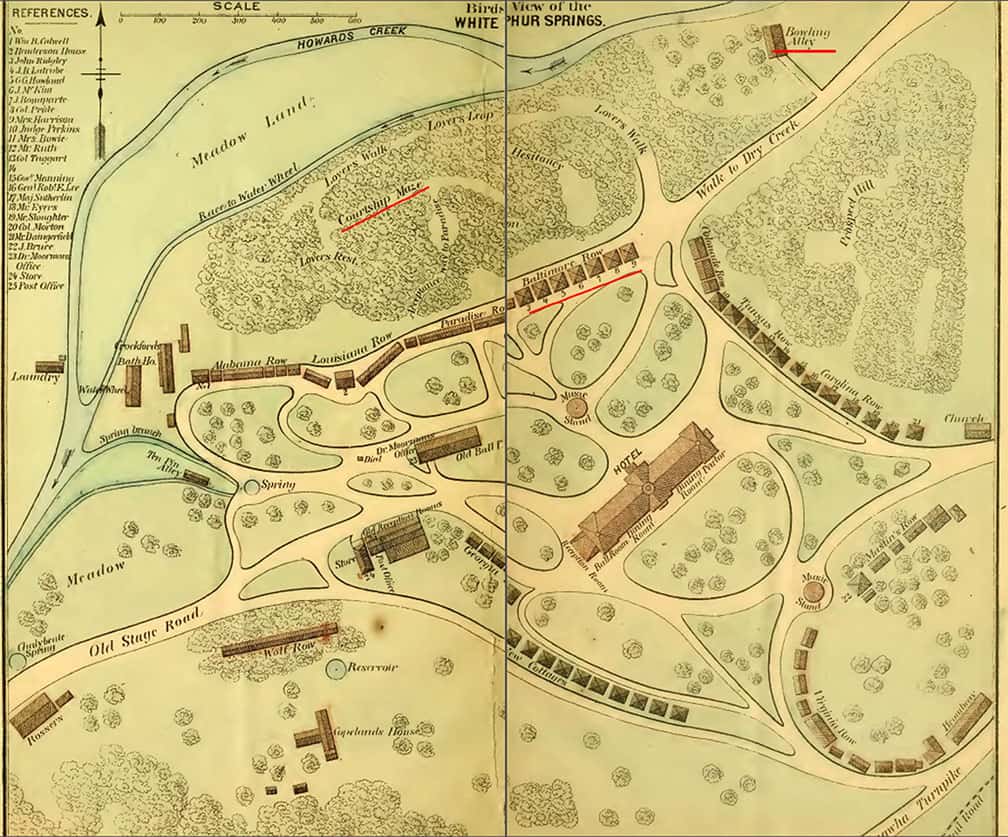

White Sulphur Springs Map – Mineral water spas were immensely popular in America from the late 1700s through the mid 1930s. In 1869 White Sulphur Springs included a bowling alley and garden mazes for residents to wander the time away between “treatment” sessions imbibing the prescribed amount of water for their condition.

That was pretty strong criticism by Dr. Lucas, but the many hundreds of books, articles and dissertations published on mineral water reveal that he was correct. But it didn’t matter, because mineral water was big, big business. Even if you couldn’t get to or afford one of the many spas that had “sprung” up around mineral water localities, by the 1870s you could get the bottled item from a local spring or nearly anywhere it could arrive by boat or rail.

White Sulphur Springs promotion – The Chesapeake and Ohio railroad finally came to White Sulphur Springs in 1873. Eventually, the famous Greenbrier Hotel was added by the R.R. company in 1913.

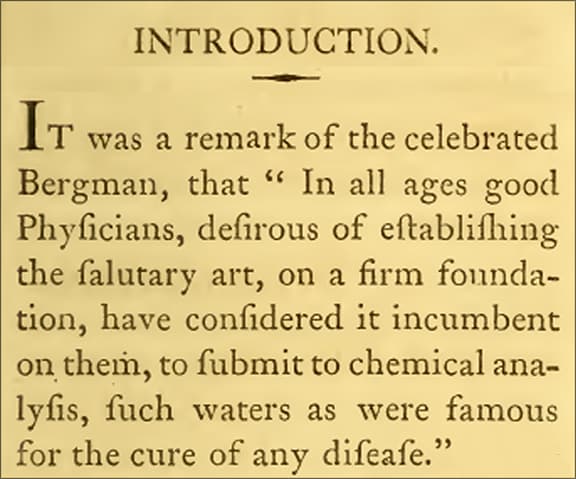

Before chemical analysis of mineral water was documented by Swedish chemist Torbern Olof Bergman (1735 -1784) there was no scientific consensus on a valid methodology. Chemists and physicians welcomed a “documented” way to analyze water content to support curative claims. In 1809, Valentine Seaman, M. D., “One of the Surgeons of the New York Hospital” wrote a 138-page book on Saratoga and Ballston Spa waters. His first words acknowledged Bergman:

Valentine Seaman intro – From “A Dissertation On The Mineral Waters of Saratoga, Including An Account Of The Waters of Ballston” V. Seaman, 1809. Regarding these waters, Seaman also notes: “I am told that during the Revolutionary War, while the troops lay at Saratoga, many of them were affected with the itch and were sent off in companies to these Springs, by which they were all cured.”

Dr. Bell in his 1831 mineral water treatise continued to support the validity of Bergman’s analytic methods: “To the celebrated chemist of Upsala, more than to any other, are we indebted for introducing system and clearness in the analysis . . .” Even with an accepted analytic method, Dr. Bell was a cautious administrator of the waters, and clearly knew that many imbibers were victims of their habits as he quoted this telling ditty:

“The stomach crammed with every dish, A tomb of roast and boiled, and flesh and fish, Where bile and wind, and phlegm, and acid jar, And all the man is one intestine war.”

It’s no wonder that the aperient (laxative) effects of magnesium and sodium sulphate-laden “bitter” water made many believers.

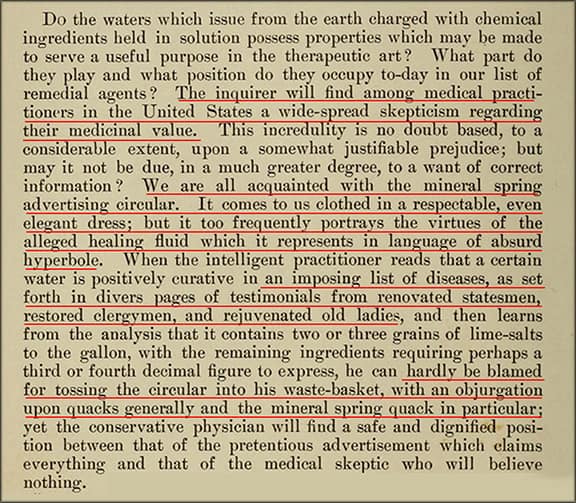

145 years after Dr. Lucas raised issues of medical quackery, criticisms of the miracles of mineral water were still being published. In his 1899 book “Mineral Waters of the United States, James K. Crook, M.D. says:

Crook criticisms – Dr. Crook’s book contains descriptions and accounts of no less than 350 mineral springs from Mt. Shasta and Pikes Peak to the West Virginian high hills.

However, no amount of science could overcome the will to believe the medical claims, nor keep throngs of “invalids” flocking to spas around the US for another 35 years. The great depression and resulting loss of wealth led to many spas’ demise. The panacea so many mineral waters offered could not cure bankruptcy.

But let’s get back to the commonplace again: Ginger Ale. Ginger was long known for its healthful properties and beneficial effects on digestion and circulation. That knowledge was perhaps concurrent with the very early beliefs in mineral water cures; in fact, during Roman times ginger was as good as gold.

The long-standing aura around ginger’s medicinal value was transferred to ginger ale when it was introduced from Ireland in 1852. By the 1860s the mineral water business was booming and bottlers quickly discovered adding the vastly popular ginger ale into their bottling line would provide a new stream of sales. After all, what could be better than healthful ginger ale made with their version of “bitterquelle”?

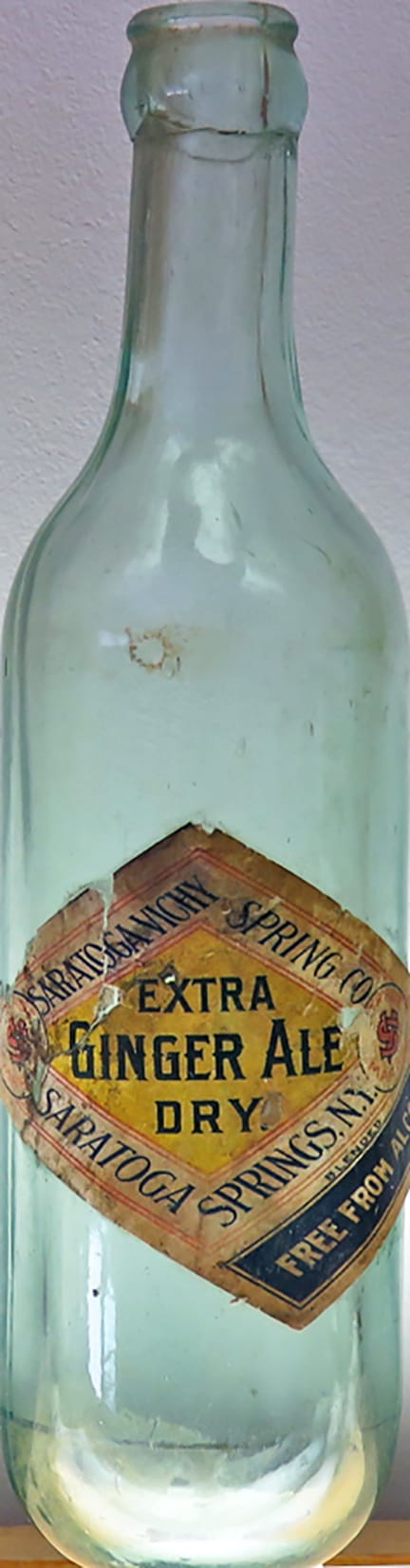

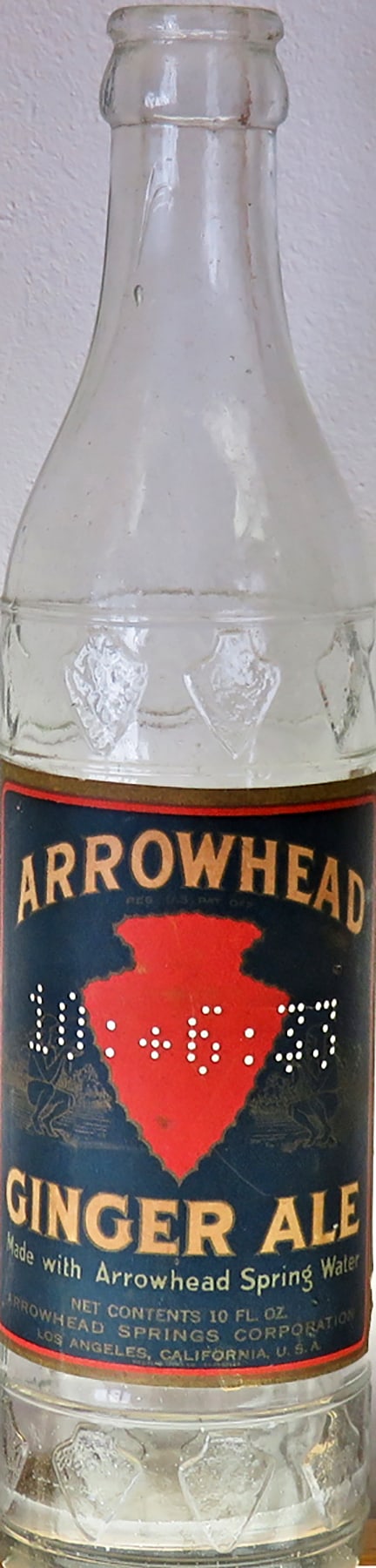

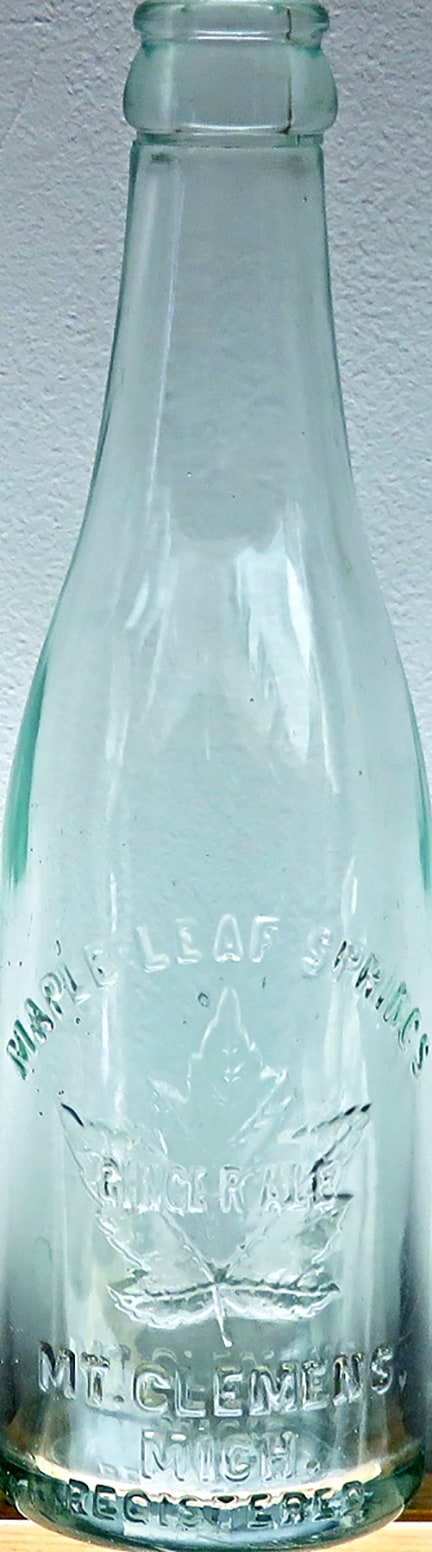

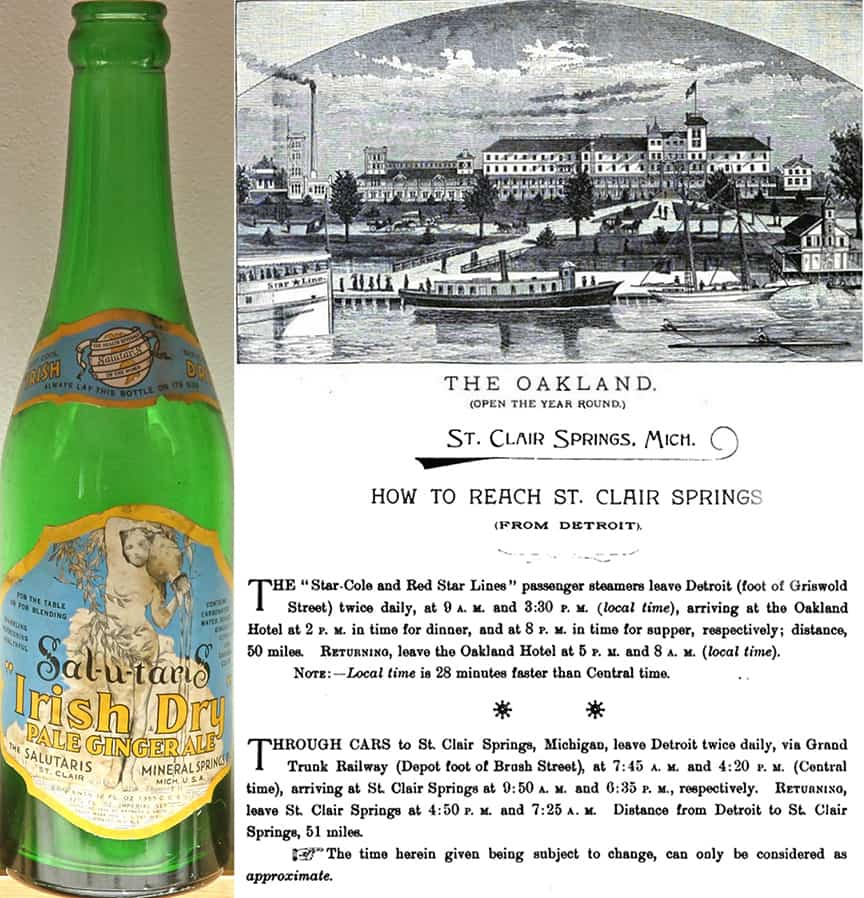

Many mineral and spring water bottlers produced ginger ale. Here’s a gallery of just a few from 1880 to 1959:

Belfast 12 -sided aqua blob – Belfast Champagne Ginger Ale & Mineral Water Co., Edinburgh, London, Paris & New York. 12 sided,; ca: 1880.

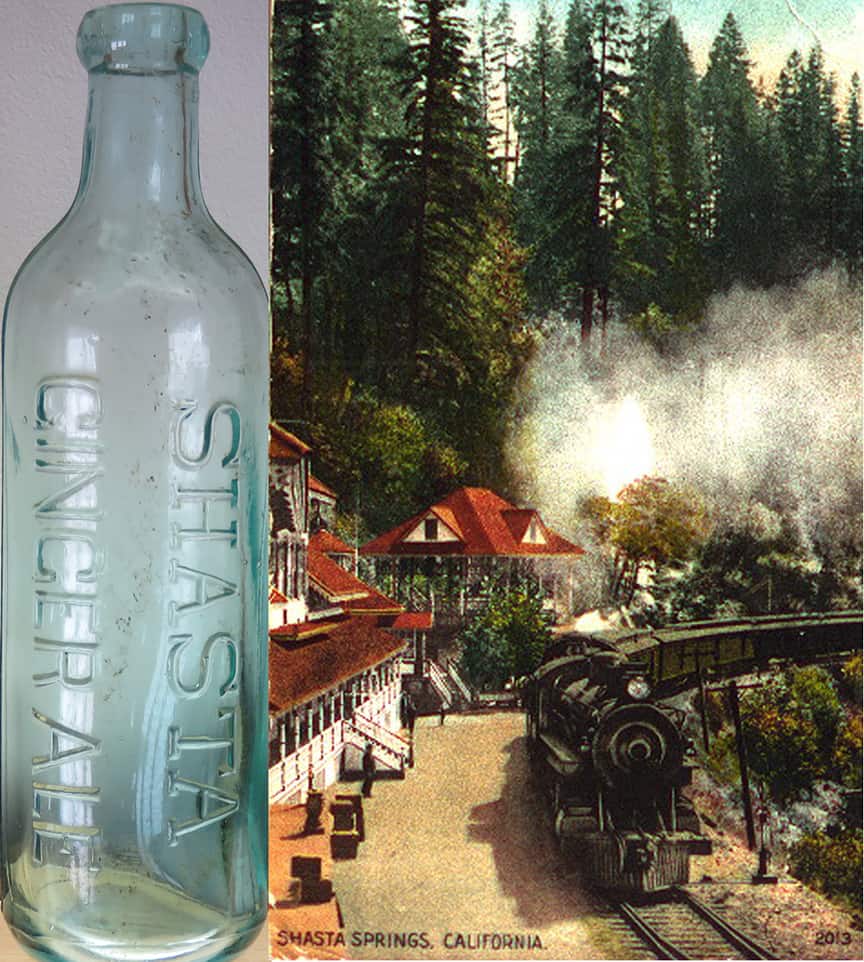

Shasta springs & postcard – “Shasta Springs, California Located on the Southern Pacific Railroad’s Shasta Scenic Route at the base of Mt. Shasta, the upper spring is at 2,363 feet. The surrounding country is wild and picturesque, and a public resort has been established for the comfort of travelers from Mt. Shasta.” Mineral Springs Health Resorts of California, Winslow Anderson, M.D., 1890.”

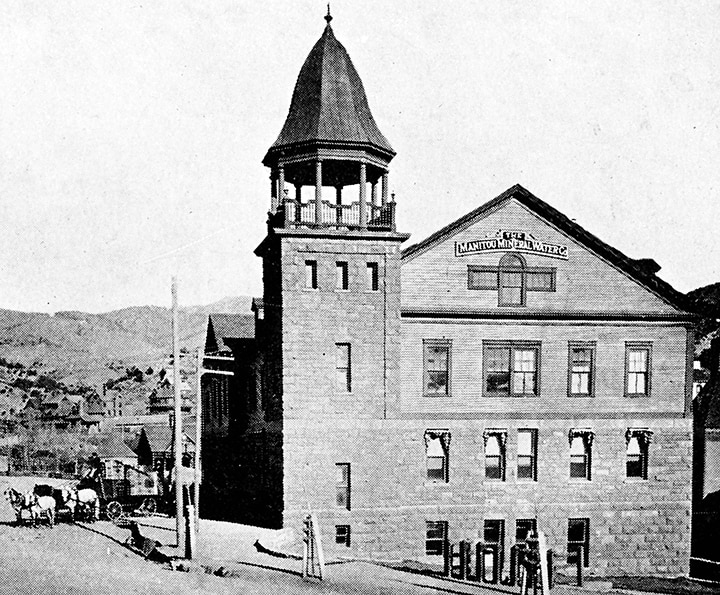

Manitou bottles – Left ca. 1880; right ca. 1920. “Manitou is situated six miles west of Colorado Springs, immediately at the foot of Pike’s Peak. Here are located the celebrated effervescent soda and iron springs which in early days gave the name of springs to the town of Colorado Springs, An electric railroad, with cars at frequent intervals, unites the two places. The town of Manitou Springs contains a permanent population of more than 2,000 souls, which number is augmented during the summer months by about 125,000 visitors from all parts of the United States and from foreign countries.” James Crook, M.D.,1899. Manitou is known to many indigenous people in North America as the Great Spirit or Creator. The springs are said to have been known to many generations of native people.

Stockton Springs – Note that this Maine bottler even went as far as to call their water source “medicinal springs.”

Saegertown bottle & label – ca 1890, European turn mold type, applied top. Many of the spa bottlers imported these olive-green turn molds, perhaps to lend a more “sophisticated air.”

East Mountain Lithia – Lithium carbonate was often found in mineral water, but in most localities it was in relatively small amounts. Current studies have been done to determine if naturally occurring lithium in water is beneficial to mental health.

Dietaide bottle & label – 1892-1905, BIMAL crown top. Given the name of the company, it is not surprising they listed the water analysis on the label.

Saratoga crown – 1892-1900. BIMAL crown top. Even after the crown top was in use for a number of years, round bottom bottles were still produced. They were seldom embossed.

Catonsville bottle & label – ca: 1920. Catonsville was located on the Frederick Turnpike, (today MD Route 144) which was built in 1780s to connect a flour mill to Baltimore. The town quickly became an easy road stop for travelers. To escape the summer heat, wealthy Baltimore residents soon built up large estates in Catonsville. They were perfect customers for a spring water business.

Arrowhead Ginger Ale – ca 1930 from Los Angeles. Springs were often associated with native Americans because the tribes readily showed the incomers where the good water was.

Maple Leaf Springs bottle – From the 1880s through the 1950s, Mt. Clemens Michigan featured no less than 13 mineral spring companies all at different locations within the town. Maple Leaf Springs (1904-1956) had a big pavilion that was both a spring house and dance floor. Mt. Clemens is also known for its early glasshouse (1836-1849?)

Salutaris Springs bottle, St Clair, MI – Bottle ca 1936. With daily boats and trains carrying customers back and forth from Detroit and points beyond, the Oakland House at Salutaris Springs boasted it was always open.

Top right: An 1842 painting of the Baltimore Row houses built at the spring in 1830. Courtesy of the Greenbrier Resort. Middle right: The original hotel at White Sulphur Springs was built in 1858. The railroad company added the Greenbrier Hotel in 1913. The original hotel, called “The Old White”, was torn down in 1922. This engraving dated 1860 was reproduced on a postcard ca. 1950. Bottom: a cut from a lithograph advertising piece, ca 1915. The bottle is ca. 1930. The earliest guests arrived at White Sulphur Springs in 1778. Between 1830-1861, five sitting presidents visited White Sulphur Springs. There is a lot more history to the Greenbrier. “

Split Rock ACL – Split Rock, Franklin Springs, NY, 1959. When Fred Suppe dug a well on his central New York state hop farm in 1888, he discovered a natural mineral water spring that was compared to the lithia springs in Europe. A number of entrepreneurs in the hamlet thought they were on to another Saratoga or Richfield Springs, but that never happened. The town originally was called Franklin Iron Works because of the blast furnace built in 1850 to process the iron ore from nearby Clinton. With the Franklin blast furnace winding down, the town was renamed to Franklin Springs in 1898 when Suppe’s new business was flowing. Between 1888 and 1970 eight different companies bottled the lithia water and made soda. Split Rock was one of those firms and Arthur Suppe took over in 1912 and bottled ginger ale and other flavors there until 1962.

Read More from Ken Previtali:

The Ginger Ale Page – Ken Previtali

Is there elegance and mystique in a milk glass soda bottle from Massachusetts?

From clear to purple or brown, that’s how irradiation runs

Don’t Bogart that Gin . . . ger Ale

The Diamond Ginger Ale Bottle House

Electric Bitters and Electrified Ginger Ale: Were they really “zapped” or was it just more quackery?

Could a mundane bottle of wine-flavored ginger ale be a descendent of a winery established in 1835?