The Dowesburgh | Albany Glass House

1785 – 1815

Part 4 of a Series

by Stephen Atkinson

11 September 2013

Leaving the town of Albany, New York, heading west on Route 20, you will arrive in Guilderland, about six miles west of Albany. Not much remains from the colonial era however, just after the Revolutionary War, Leenert De’Nuefville, who had raised a half million pounds towards the Colonists cause against England, was in need of cash again.

Leeenert was of Dutch origon and knew that the only way early villages could survive was to establish manufactories.

Leeenert was of Dutch origon and knew that the only way early villages could survive was to establish manufactories. Leenert was contacted by a Dutchman, Johannes Heefke, who earlier in the year of 1782, wrote John Adams the following letter from the archives of the Library of Congress in the Adams family papers:

Johannes Heefke to John Adams, Amsterdam, 7 June 1782

Distinguished Sir!

For a long time I have had an ardent and avid desire to be in North America, but never did my wish come true: for three long months it seemed as if I would be able to get there; I asked Mr. Willem Hooft (who knows me) whether this honorable gentleman might help me. This particular gentleman sent me to Mr. Jean de Neufville, who did not only allow me this favor graciously but also promised to help me once I got there. Nonetheless I had to wait two more months before a ship of this honorable gentleman left thereto. But alas! When the two months had gone by he notified me that he had neither ship nor opportunity to help me. So I pondered my problem and tried to think of a solution. In the meantime I found out that there is a gentleman here who has a considerable amount of vacant and uncultivated land in North America for sale, both in Canada and north of Albany on the river which leads to New York, but so far he has not sold anything yet. Part of these lands could well be used by glassblowers.

Sadly, I lack the means, for if I had them I would be able in a few years to turn thousands of acres of fallow land into fertile land. I have run a strong business in my country around Mecklenburg, but I had to discontinue it because of a lack of wood; I could run the most beautiful business if only I knew of a way to help my lack of means. Great minister, do not be angry with a man who begs you for a favor. I know that your excellency has a charitable disposition and that you like to make people happy; and I would be greatly helped by your mediation and distinction, and I would be one of the happiest people in the world; I would show that I would know how to get the most from such a piece of land. Thus your excellency would not have to be ashamed of your charity, but you would have nothing but pleasure from it. You can help me in the following way: by mediating, and through your distinction I would be able to pay off in the next few years the gentleman who has his land for sale. It will be good business for him, too. And he could give me a loan, which I would pay off the next two years with ease.

The piece of land by the big river that is cut through by a small river would be very suitable for such an enterprise. It amounts to 15,000 acres and would cost f12,000 plus the money that would be required for such an enterprise, which would amount to 7,000. Because I would need more than thirty glassblowers of whom the tools and transport would be the biggest burden. However, once they would get to work, they would be able to produce 1,000 to 1,200 cases of glass in four years. With the exception of the many thousands of bottles that would be counted as wages, I could in this way (if I charged 10 for every case) save 10,000, which I would use to pay off the land in four years. I would be such a happy man if I could do that! All because of your excellency! I do not need more than upwards of 2,000 florins in hand, and with this I can buy several pieces of decent land, which would be sincere proof of my honest and decent livelihood and existence.

The rest could, if you agree with this, be sent or be delivered by an emissary. The same person could henceforth inspect my enterprise. An honest man is not afraid of such inspections. Honorable great minister! Of a happy country! It would be easy for your honorable excellency to help me because you are a man with so much distinction (and you are a man who has been here twelve years and has wrestled with all imaginable adversity). I will not lack in vigilance. With good reason I can flatter myself that I know the economy and the particularities of the land and the cultivation of the land; in addition I understand the various arts. Once again, great minister, I beg you to make my wish come true. I will accept your decision with resignation. I am your humble servant. Please, your excellency, you can send me your decision in a few words. I beg you to forgive me for these liberties I took. Your excellency, In case your excellency honors me with a letter, my address is in care of widow Altinaa at the Achter Burchwal at the Emder or Frisian post office.

Your humble servant,

Jan Heefke

No help from John Adams was forth coming, however this did not stop the plan to establish a glasshouse. In May 1785, Heefke and his partner Ferdinand Walfahrt signed a contract on May 12th, 1785 with Leendert de Neufville, Jean de Neufville’s son, to establish a glasshouse at Dowesburgh (now Guilderland), New York, about eight miles from Albany.

The glass house was located near the banks of the Hungerskill River just south of the stage road leading eastward towards Albany.

Experienced glass workmen had been brought from Germany, and the building of the new factory had begun in the winter of 1786. The glass house was located near the banks of the Hungerskill River just south of the stage road leading eastward towards Albany. Heefke named these early works the Dowesburgh Glass House. The blowing of glass commensed in the spring of 1786 as the glass blowers from the Palatinate region from Germany began to produce glass. They made hollow ware (utility bottles) but the main output was window glass. Guilderland, in the mid 1700’s, was still a wilderness and was chosen for glass-making rather than a location nearer to Albany, where civilization and transportation were close at hand. The reason is quite simple, for the present town of Guilderland had all the raw material necessary for the manufacture of glass along with the necessary wood for the furnaces and potash for the making of the glass. Waterpower from the Hungerskill, and an abundant supply of sandy soil were all the ingredients needed for this venture.

The aerial photo below from Google earth shows the exact location of the colonial glass works in present day Guilderland, New York, just 8 miles west of Albany New York.

The works survived for two years but soon Heefke and his partner Walfahrt were running out of capital to run the factory. They along with de’Nuefville, appealed to the State of New York for 30,000 pounds in order to keep the glass works going. Their initial appeal was rejected by the state. However, in 1789, Leenert de Neufville again solicited the legislature for funds, and on March 3, 1789, both the Senate and the Assembly granted him a loan of 1,500 pounds to carry on the glass works. As was the case with so many glass houses before them, they soon began to experience additional monetary problems and in 1791, the glass works were bankrupt and out of business. Leenert de Neufville ultimately became depressed and abandoned his interests in the glass works. He died in 1796 in Albany, leaving his widow destitute.

as the state of New York realized it was very important to have this manufactory located near the capitol city

This was not the end of the venture as the state of New York realized it was very important to have this manufactory located near the capitol city and soon a company was formed. In 1793, a petition for state aid for the Glass House was submitted in the name of McClallen, McGregor & Company and the principals were James Caldwell and Christopher Batterman, later Sheriff Batterman of Anti-Rent War fame. The State granted a loan of 3,000 pounds for eight years; three interest free, and five years at five percent. In the year 1795, the Glass House was twice reorganized, first as McGregor & Co., and then as Thomas Mather & Co.

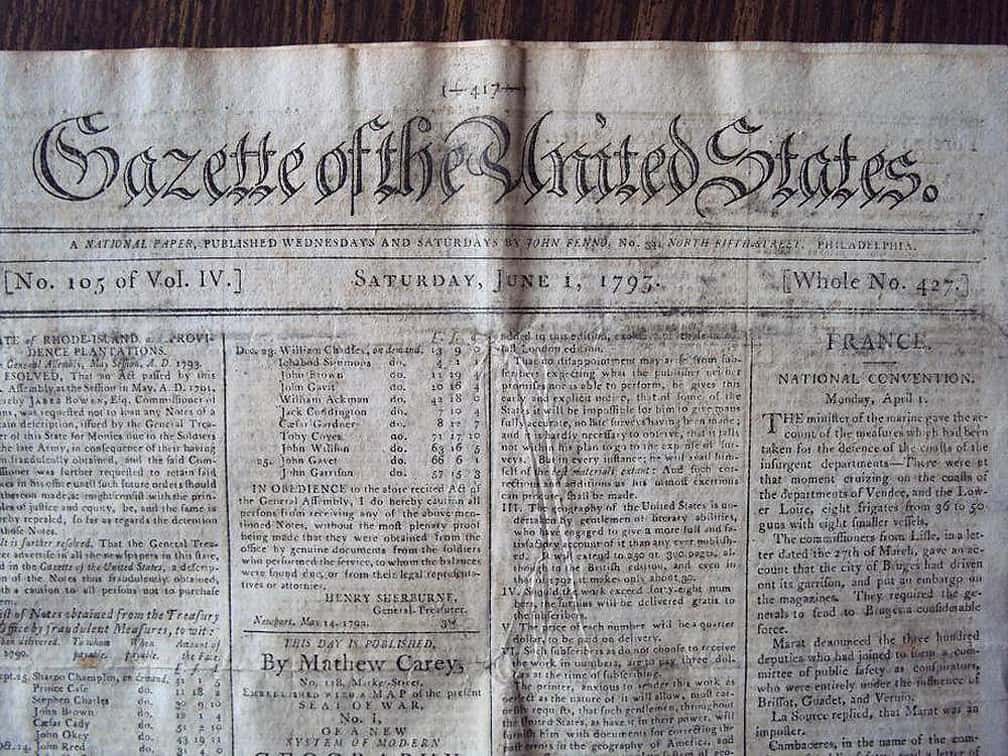

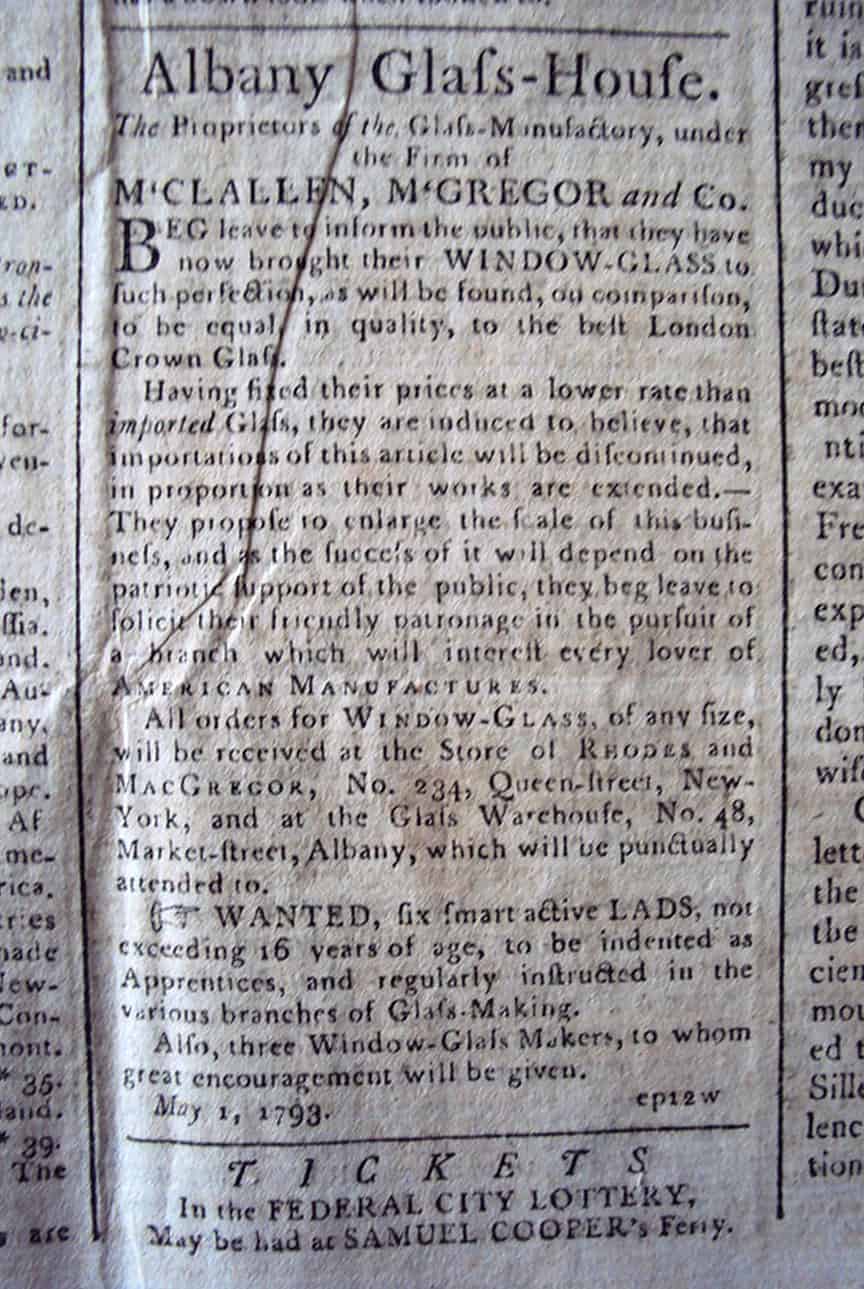

Below is an advertisement from the June 1st 1793 edition of The United States Gazette Newspaper out of Philadelphia from my collection.

I am sure that Demijohns like the ones pictured below, were made at this factory.

In 1796, the state Legislature passed an act that exempted the company and the workers from all taxes for five years as encouragement for consolidating the glass works into a permanent manufacturing town. It was named Hamilton, in honor of Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasurer, who was influential in obtaining a $3,000 grant for the widow de Neufville. In 1797, the company was again reorganized under the name of of the Hamilton Manufacturing Society. The directors of this new company were the following gentleman; Jeremiah Van Rensselaer, John Sanders, Abraham Staats, and Thomas Mather of future Connecticut glass house fame.

By 1813, the glass works were producing 500,000 feet of window glass annually, along with utility bottles and demijohns.

The glass works were run successfully for 17 years by this firm which changed from time to time. By 1813, the glass works were producing 500,000 feet of window glass annually, along with utility bottles and demijohns. The factory employed over 50 workers, whom were living in company houses, of which two can be seen today along Route 20, then known as the Great Western Turnpike. Company housing was typical of the times when people lived as close to work as possible. In addition to the company housing, the glass works also operated a company store, where all necessities, such as food and clothing, were purchased at a premium price with company script. In 1815, due to the lack of wood which had been depleted and the sand deposits which were running out, glass-making in Guilderland factory had ceased.

The success of these glass works inspired glass making throughout the State of New York

Glass fragments found in the Hungerskill stream show that the color of glass that was being produced at the factory was dark green for hollow ware but pale green in color for the flat crown window glass which was also found in abundance. The type of glassware and bottles made here was very utilitarian in nature but I am sure offhand pieces were also made at these works just as they were at others before and after them. Window glass was the mainstay of production as their glass was shipped away as far as Baltimore to the south and all of New England to the East and North. These glass works were the last of the 18th century incorporated manufactories in the State of New York. The success of these glass works inspired glass making throughout the State of New York and the nineteenth century would see over 30 additional glass works constructed in all regions of the state.

About Stephen Atkinson

Stephen Atkinson, from Sewell, New Jersey has been collecting bottles and glass since he was 12 years old. He once dug an original EG Booz figural cabin bottle on Norris Street in Mantua, New Jersey in 1972 at 12 years old and traded it for six bitters bottles. Fast forward to 2012 and Stephen bought the exact bottle back at an estate auction in New Jersey!

His passion is for pre-1880 glass, as the majority of his collection consists of historical flasks, colonial era chestnut bottles, and whimsical end of day pieces of glass. He also has three rare T.W. Dyott bottles, an original Dr. Robertson’s family medicine; one of the rarest collectable American bottles, a T.W. Dyott vial bottle dug by Chris Rowell and a paper labeled T.W. Dyott bottle. He has researched many southern New Jersey glass works first hand by locating the original factory sites. The best piece in his collection is the Wistarburgh Glass Company ledger showing monies paid out to Caspar Wistar’s Children and their husbands and wives.

Read more Stephen Atkinson articles in this series:

The New York State Glass Factories | Preface to a Series

Newburgh (Glass House Co.) 1751-1759 | Part 1

Brooklyn (Glass House Co.) 1754-1758 | Part 2