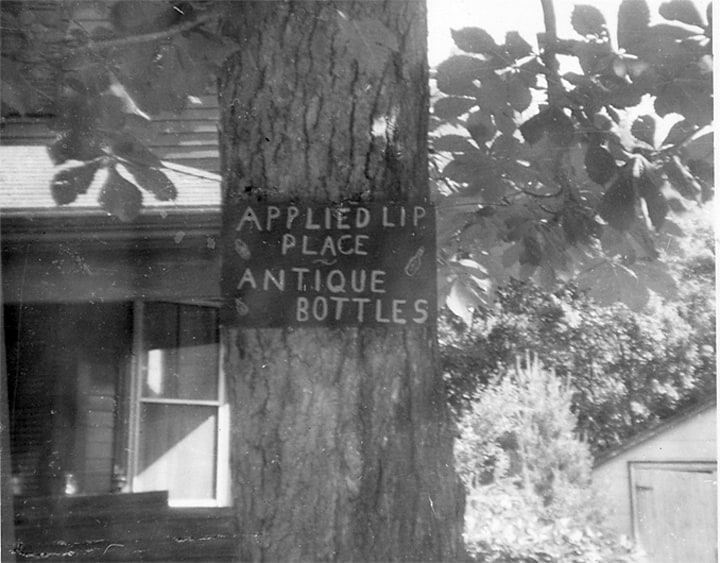

By 14 I had my own bottle shop in our cellar, a sign on the tree out front, had a table at the local flea markets, went to several major auctions at Bob Skinner’s, was advertising in Old Bottle magazine and was a paid-up FOHBC ‘at-large’ member.

Dear Mr. Meyer,

I just spent a cold, crusty Maine Saturday poring over your Peachridge blog and website. It is all very inspiring.

I grew up in southeastern Massachusetts and starting digging bottles in the neighborhood at age 12 (ie. 1976). By 14 I had my own bottle shop in our cellar, a sign on the tree out front (see above), had a table at the local flea markets, went to several major auctions at Bob Skinner’s, was advertising in Old Bottle magazine and was a paid-up FOHBC ‘at-large’ member. After shipping out to college in 1982 (UMaine) I took a break and now at 48 am circling back a bit, hence these observations.

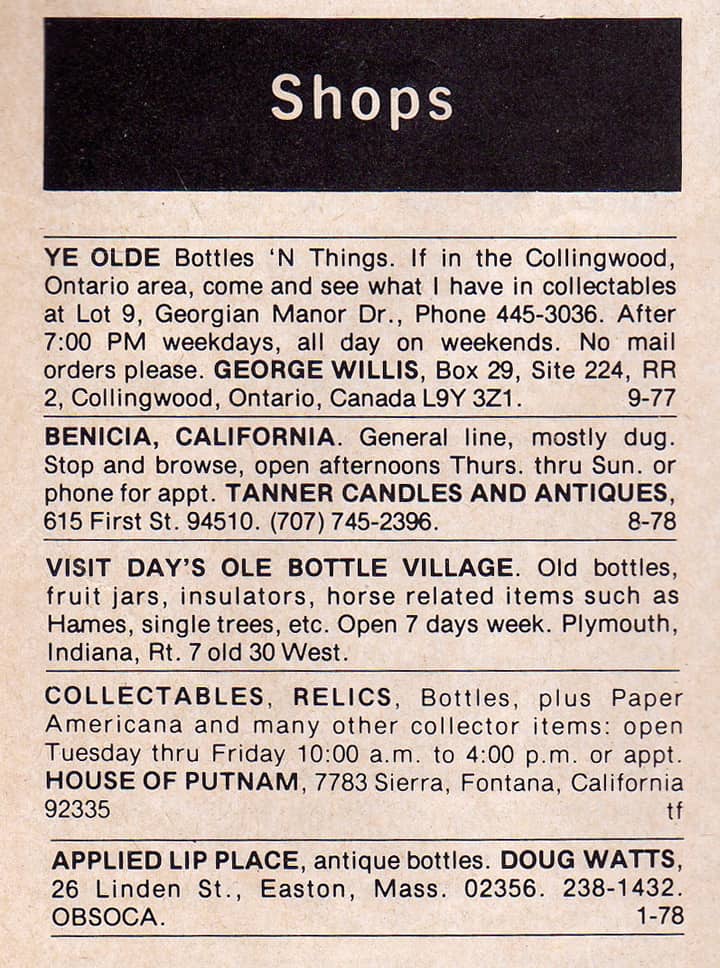

Scan from Old Bottle Magazine in 1977 or so when I first advertised my little bottle shop when I was 13.

1. My brother, cousins and I were collecting in the late 1970s as kids, which was when the pursuit perhaps peaked in general popularity, certainly as gauged by average price. The Charlie Gardner auction at Bob Skinner’s was a catapult. Interestingly, the prices of low to medium range bottles today have not changed much in the past 35 years. A Doyle’s Hop Bitters is still about $30, a Drakes Plantation is $50, a run of the mill olive amber cornucopia and urn flask is still about $75; an aqua, smooth-based Union Clasped Hands is still about $50. Antique dealers are still trying to get $20 for a clean Hood’s sarsaparilla. In this respect, antique bottles are a terrible investment! Using the price of gasoline as a metric, a normal National Bitters or Indian Queen should cost nearly $1,200 today. If you bought a Drake’s Plantation bitters for $55 in 1978 and held onto it for all this time, it would only be worth about $15 today in 1978 dollars. But I think this is an incredibly good thing since it keeps fascinating old bottles well within the means of the most modestly endowed collector, ie. kids. And you can always go digging.

Jar of Shards. READ: Bottle Shards in Window Jars – I like it!

2. I like your blog piece (Read: Bottle Shards in Window Jars) about keeping shards of oddball or unknown bottles even if they aren’t whole. This is important since it re-emphasizes the role of bottle diggers and collectors as historic archaeologists and preservationists. Regular archaeologists don’t toss shards — they are the purpose of the excavation. In my intense bottle digging phase (1975-1982) we were ‘trained’ by the market to leave behind in the dirt anything that wasn’t whole, displayable and saleable. Part of it’s an education thing, part of it might have been our youth, but there is a lesson here. Adding another scuffed up but whole root beer colored Drake’s Plantation to the world doesn’t add much (maybe $20 in your pocket) — but that shard of a really weird, unknown piece might be the key to a long lost puzzle or at least a new bread crumb along the way. Toss it, and all information is lost.

Doug, Allan and Tim Watts in summer 1978 prepping for probe-rodding several 1850s cellar holes in the hillside behind them in East Corinth, Vermont. We never heard a single clink of glass after two days of probing down to six feet. We could never find the outhouses.

3. FOHBC at its outset had a mission (or at least I perceived it this way at 14) to create a sense of legitimacy to both the pursuit and end product of the efforts of a lot of disparate diggers and enthusiasts nation-wide. In the 1970s bottle collecting had a legitimacy problem – straight antique dealers felt a bit awkward setting up a table next to a bunch of grungy blue collar people (or kids) who got themselves happily muddy every weekend digging in dirt and put their newfound wares on a flimsy card table in a cow pasture. Bob Skinner and Norman Heckler at Skinner’s in Bolton, Mass. did a lot to change this – certainly the prices and turn-outs they were getting helped change perceptions amongst the more fastidious. But I think the biggest contribution Bob made, and Norm has now made many times over, is that a lot of these glass objects are truly deserving consideration as legitimate folk-art objects, even if they were ultimately intended, paid for and designed to serve a purely mercantile interest. Art and artistic expression will always squeeze itself like toothpaste out of the weirdest crevices. This is not something a 14 year-old fiendishly digging for a Berkshire Bitters might appreciate, but can easily be seen by the same person a few decades later.

4. Lastly, I note your keen interest in obscure bitters bottles. At 14 I was advised by older collectors to find and focus on one area and dig in as deep as possible. So I decided to focus on free sample bottles. My rule was it had to be embossed ‘sample’ or ‘trial size’ or be so small that it couldn’t be anything but a free sample (thus eliminating tiny pill or perfume bottles which were actually intended to be that size). Sample bitters bottles are the coin of the realm for this narrow field. The best embossed free sample bitters I have is a tiny Hentz’s Curative Bitters — Free Sample – which I bought from Tommy Mitchiner through the Old Bottle Magazine in 1978. Embossed sample bitters are really hard to find and easily confused from merely ‘small-sized’ bitters bottles which I believe were used post-1900 as flavorants for mixed drinks (ie. Angostura bitters, Abbott’s bitters). The key I’ve used as an indicator of a true ‘free sample’ bitters is the Dr. Harter’s wild cherry bitters. It’s an exactly replica of the one quart bottle but is only 3.5 inches tall; I think that was clearly a give-a-away at a medicine show. So this is kind of a request, but it would be cool if sometime you could do a little photo spread on your blog of some of the sample-sized bitters bottles in your collection and maybe a call-out to your other bitters fiends for what they might have kicking around in the sample-sized realm. They are a genre unto themselves.

Thanks for all your work,

Douglas Watts

Augusta, Maine

P.S. Here’s a funny story about Bob Skinner and Norm Heckler. Our dad was a landscaper but also pruned apple trees in the winter in Bolton, Mass., just a short distance from Bob’s auction gallery in Bolton. My brother and I bugged our dad drive us 50 miles to a few of their first post-Charlie Gardner bottle auctions. We would get our little gold plastic auction paddles and go through the whole preview and look at everything and figure how to spend our $50. I was 14, my brother was 16, and we knew the going price of everything, so we would sometimes bid over what we actually had for money, thinking that if we got it dirt cheap, we could get the money from dad to pay Bob Skinner and then sell it to the lurkers in the parking lot and get the paying price back and pay back dad. Bob and Norm would switch off at the gavel every hour or so. We loved the auction patter that Bob and Norm used and would copy it all the way home. After the first few auctions we had perfect Bob Skinner and Norm Heckler impersonations down. Neither Bob or Norm were hard sell. It was clear Norm knew exactly what a specific bottle should go for: he was and is an encyclopedia. So one day I was bidding and bidding and bidding all day but always got outbid by $10 at the very end by some guy in the back row because me and Timmy only had $50 between us. And finally I hung on to the bitter end and had the high bid on a deep olive amber cornucopia and urn flask for $80 and Norm looked around the room and said, “I have $80 in the front … is there any advance? …. And it is, $80 to 49.” And then Norm looked right down at me and said, “That’s 80 to 49.” And then the whole room burst in applause since everyone had seen us kids trying and trying to buy something all day but never succeeding. Then we thought, oh crap, we actually bought it. Gotta go talk to Dad and get some more money. He was out in the parking lot yakking with Fred Schwiekowicz, a bottle dealer from around Brockton, Mass. Dad paid the $30 extra that we didn’t have but told us we’d have to work it off mowing lawns and digging holes. Which we did. But we had a real Early American flask !!!

![]() Doug.. I am so grateful for you taking the time to share some stories and insights. This is what it is all about. Thank you so much. Stay tuned. Ferdinand

Doug.. I am so grateful for you taking the time to share some stories and insights. This is what it is all about. Thank you so much. Stay tuned. Ferdinand