Bunker Hill Monument Figural Colognes

05 February 2012 (R•111215) (R•022319)

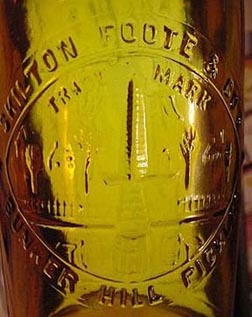

![]() Yesterday I spent the day recording and moving some new bottle acquisitions around. One bottle that was a conversation piece on facebook was my new citron, SKILTON, FOOTE & COMPANY BUNKER HILL PICKLES / TRADE MARK, (Motif of monument) that I won in the Heckler | Thomas McCandless Auction III. This bottle will join my color run of lighthouses pictured above.

Yesterday I spent the day recording and moving some new bottle acquisitions around. One bottle that was a conversation piece on facebook was my new citron, SKILTON, FOOTE & COMPANY BUNKER HILL PICKLES / TRADE MARK, (Motif of monument) that I won in the Heckler | Thomas McCandless Auction III. This bottle will join my color run of lighthouses pictured above.

The second bottle was a short, square (have not seen a square Bunker Hill before) yellow/amber BUNKER HILL BRAND SKILTON, FOOTE & COMPANY BUNKER HILL PICKLES / TRADE MARK, (Motif of monument) that I purchased at the 49er Bottle Show in Auburn, California this past December. The Heckler bottle was made in the form of the Cape May Lighthouse built in 1859 at Cape May, New Jersey. This is a great bottle in my mind because of the dual Cape May Lighthouse form and and Bunker Hill Monument embossing. This got me thinking of my Monument Colognes and specifically the Bunker Hill reference.

The second bottle was a short, square (have not seen a square Bunker Hill before) yellow/amber BUNKER HILL BRAND SKILTON, FOOTE & COMPANY BUNKER HILL PICKLES / TRADE MARK, (Motif of monument) that I purchased at the 49er Bottle Show in Auburn, California this past December. The Heckler bottle was made in the form of the Cape May Lighthouse built in 1859 at Cape May, New Jersey. This is a great bottle in my mind because of the dual Cape May Lighthouse form and and Bunker Hill Monument embossing. This got me thinking of my Monument Colognes and specifically the Bunker Hill reference.

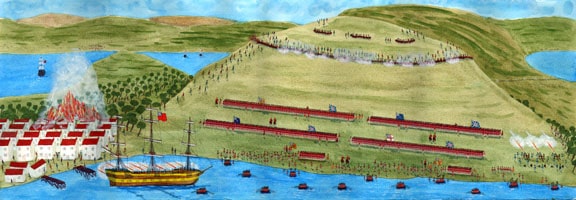

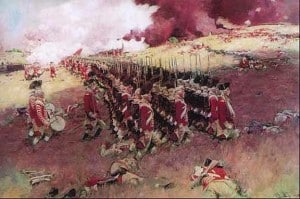

The first battle of the Revolutionary War was fought on June 17th, 1775, at Bunker Hill during the Siege of Boston. When the war began, the British knew the importance of the city of Boston to the American colonists and wanted to gain control of it early on. Across the Charles River, in Boston, stood two hills on the Charlestown Peninsula – Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill. 1500 American colonists were sent to establish defensive positions on Bunker Hill. In the space of just two hours, 2,500 British soldiers charged the Colonial patriots (rebels) three separate times. Fighting from V-shaped trenches hastily built overnight, the Colonial forces drove back the first two attacks causing heavy losses. On the third attempt, the British commander ordered a bayonet charge to seize Breed’s Hill. Many of the American militias, lacking bayonets on the their muskets and running short of ammunition, were forced to fall back to their fortified position in Cambridge. The British controlled Bunker Hill.

The first battle of the Revolutionary War was fought on June 17th, 1775, at Bunker Hill during the Siege of Boston. When the war began, the British knew the importance of the city of Boston to the American colonists and wanted to gain control of it early on. Across the Charles River, in Boston, stood two hills on the Charlestown Peninsula – Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill. 1500 American colonists were sent to establish defensive positions on Bunker Hill. In the space of just two hours, 2,500 British soldiers charged the Colonial patriots (rebels) three separate times. Fighting from V-shaped trenches hastily built overnight, the Colonial forces drove back the first two attacks causing heavy losses. On the third attempt, the British commander ordered a bayonet charge to seize Breed’s Hill. Many of the American militias, lacking bayonets on the their muskets and running short of ammunition, were forced to fall back to their fortified position in Cambridge. The British controlled Bunker Hill.

The American Colonists sustained their greatest number of casualties while in retreat on Bunker Hill. The British army suffered even more casualties, though – forty percent of their forces, including officers, were lost. Great Britain had won the first important battle of the war. The American troops, however, had learned that the British army was not invincible in traditional warfare. The Battle of Bunker Hill became a symbol of national pride and a rallying-point of the rebellion against British rule.

The American Colonists sustained their greatest number of casualties while in retreat on Bunker Hill. The British army suffered even more casualties, though – forty percent of their forces, including officers, were lost. Great Britain had won the first important battle of the war. The American troops, however, had learned that the British army was not invincible in traditional warfare. The Battle of Bunker Hill became a symbol of national pride and a rallying-point of the rebellion against British rule.

In researching Monument Colognes I came across a really great article previously published in Antique Bottle and Glass Collector by Harold Leonard Krevolin under the previous tenure of Glass Works Auctions Jim Hagenbuch. Antique Bottle and Glass Collector is now published by John Pastor of American Glass Gallery. I have reprinted it below as it really answers the many questions we have about this bottle.

FIGURING OUT FIGURAL BOTTLES

By Harold Leonard Krevolin

THE BUNKER HILL MONUMENT FIGURALS: ARE THEY OR AREN’T THEY?

INTRODUCTION

This article has two purposes. The first is to explore the various sources of information to see what figural, if any, represent the Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown, Massachusetts. The other is to help the reader to become better acquainted with these bottles. While there is an abundance of information on the monument the same is not true of the figurals. This situation provided the writer with the motivation to fill this gap.

As a beginning, data was obtained from the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, Boston National Historical Park, Chalestown Navy Yard, Boston (Charlestown), Massachusetts. The materials were helpful in becoming informed about the monument and its history. The information was studied and compared with the figurals; this started some initial thinking about the relationship between the bottles and the monument.

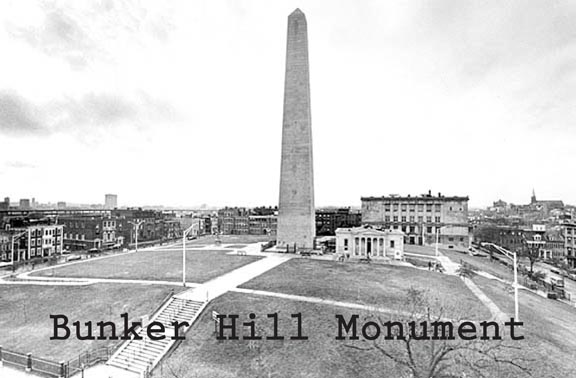

The next step was a trip to Charlestown to study the 221 foot 5 inches tall structure firsthand. This provided the opportunity to answer questions not in the materials sent by the Department of the Interior and other sources. It offered the opportunity to get a better grasp of its structural make-up and aesthetic characteristics. It was discovered later in the investigation that this close scrutiny of the monument was invaluable as it and the bottles were being compared.

It is interesting to note the dichotomy that exists, in calling the figurals Bunker Hill Monument and monument colognes or just monuments. As far back as 1926 with Stephen Van Rensselaer’s Early American Bottles and Flasks, (J. Edmund Edwards, Publisher) and more recently Helen McKearin and Kenneth M. Wilson’s American Bottles and Flasks and Their Ancestry (1978) (Crown Publisher, Inc.), there is no reference to the figurals as the Bunker Hill Monument. This is also evident in auction catalogues from such sources as Glass Works Auctions, Harmer Rooke Galeries, and Robert W. Skinners, Inc., and others. As a sidelight, there is a lack of consistency in the bottle periodicals during the 1960’s to the present. At times, the bottles are referred to as monuments and other times Bunker Hill Monuments.

In contrast, there is a sampling of books that use the words Bunker Hill Monument or just Bunker Hill to describe these figurals. This occurred as early as 1949 in E. McCamly Belnap’s Milk Glass (Crown Publishers, Inc.), Otha D. Wearin’s Statues That Pour – The Story of Character Bottles (1965) (Wallace Homestead Book Company), Jewel and Arthur Umberger’s Collectible Character Bottles (1969) (Corker Book Company), and Cecil Munsey’s The Illustrated Guide to Collecting Bottles (1970) (Hawthorn Books, Inc.). This contradictory situation simply points to the lack of certainty about what these figurals should be called. This was recently pointed out when a well-known auction catalogue that included bottles, flasks, and inks called the figural and Baltimore Monument Cologne. (Note: No auction houses previously cited) Through an examination of the evidence, a more definitive conclusive will arise.

In order to determine whether the figurals are or are not the Bunker Hill Monument, a progression of information and reaction has been developed. First, the reader will be given a detailed description of the figurals. This will assist in arriving at a better understanding of the figurals whether the answer to this article’s question is “yes”, “no” or even “maybe”.

The next section will deal with the reaction to the figurals’ descriptions as related to the monument. Certain significant descriptive elements will be used to make the comparisons. These will include closure, surface, windows, date, and origin.

From this discussion a two-part conclusion will be offered. The first will answer the article’s question. The second will give a review of the bottles, as figurals with no attempt to relate them to the Bunker Hill Monument. This is important since a figural must stand on its own value to be collectible or saleable.

Finally, in keeping with the format or articles in this column, a value scale will be presented for those figurals that are known to exist. The listing is comprehensive and as new examples surface they can be easily put in the scale. It is felt that any new bottles that will affect value will have to do with color. For example, if a yellow or red example were found one could be sure they would be at least rare or very scarce. The possibility of an aqua being found is not far fetched. Depending on circumstances, it could be quite low. When unusual color is not a consideration, other factors such as rarity and quality of glass need to be considered.

DESCRIPTION OF BOTTLES

Shape

The bottle is in the shape of a partial obelisk with a square base. The four-sided shaft that has tapered ends on the top with the bottle’s rounded neck and opening. A completed obelisk should have the four tapered sides ending with a pyramidal point on its top.

Size

There are two basic size groupings. The first group includes the largest that are approximately twelve inches in height and have a square base that is close to two and one-half inches. Those with obelisk glass stoppers are about fourteen and one-half inches tall.

The other group range in height from slightly over five to nearly ten inches. Like the larger size, the bases are square, but are not as uniform in size since their heights vary. Some examples of height in this group are: clear – 5 1/8, 6 3/8, 8, 9 1/4, 9 7/8; white milk glass – 6 1/2, 8, 9 1/8, 9 3/4; color – 6 5/8, 7 3/4, 8 1/2, 9 1/16.

Closure

A cork is inserted in all small sizes. A cork and glass closure is used in the larger figurals. The glass closure is in the shape of an obelisk. Its ground rounded base fits into a similar surface, inside the neck of the bottle.

Opening

The opening of the bottle is usually a tooled flared or flanged lip.

Surface

The embossing on some of the smaller and all the largest size figurals is bold. This protrudes slightly. There are smaller examples that have low relief through the fine raised lines that separate each “stone”. All examples have principally horizontal rectangular and square shaped stones. The square stones often become rectangular due to the narrowing of each side as the bottle tapers to the top.

The large size figurals and smaller examples, having high relief stones, are laid in courses having two horizontal rectangular stones on one layer and two squares on either side of a rectangle on another. The large size examples, having spaces or “windows” above the door, have their windows between two rectangular stones. The stones next to each other of the uppermost windows on each of the four sides differ. The front having the door and also reverse has one rectangular stone on each side of window. On the other two sides of bottle, the upper windows have two vertical rectangles on their sides.

The smaller boldly embossed bottles have stone patterns similar to larger bottle. They usually do not have windows, but the effect of stone surface changes near their recessed doors. The two courses of stone, which comprise the height of the door, have one square stone on each side. On the larger size, there is a rectangular stone on two layers next to door.

In the low relief examples each of the four sides starts at the base with three horizontal rectangular stones. Above it are four stones including two rectangular in the middle and square at each end. The next course returns to three rectangles. The six windows above the door have a rectangle and square on each side. There is another window on each side of upper portion of bottle. It has two stones on each side. They are a square with a vertical rectangle on each end. The extended door has stones laid in three courses. The first and third level has one rectangle on each side. The second course has two squares.

Bottom

Except for one known example having an open pontil, all have a bottom that either has a concave ore circular area that bulges slightly. The smaller figurals that have low relief stone work do have a concave area on their bottom. Most other, both large and small, have a circular area with a bulge.

The pontiled figural was owned by George McKearin and then sold at a Harmer Rooke Gallery Auction from the Richard Doyle Collection. It is of the twelve-inch variety and has a blue-purple color.

Color

Most small and large figurals have been found in clear, blues, greens, white milk glass, and opalescent glass. An amber example in the large size exists, and is very scarce. The color amethyst has been found in the smaller size grouping.

Contents

It is usually concurred that most of these figurals held cologne. This is gleaned from labels and perfumery revenue stamps found on all examples except the larger colored bottles. One could speculate that the larger examples held another liquid. Those with ground glass stoppers appear to be decanters and might have contained wine.

Date

The pontiled example is dated in the Harmer Rooke Gallery catalogue as Ca. 1841-1850. Putting this figural aside, all others are Ca. 1860-1900. One of the procedures for dating this figural is through the use of label styles and revenue stamps that were used from 1862-1883 and revived 1898-1900. It is not uncommon to find these labels and stamps on most smaller examples and the large clear size. Those that are excluded include the larger size versions that are colored and have bold stone embossing. This includes those in white mild glass and those having the obelisk stoppers.

Another indicator of age is the appearance of bottle. Mold seams and lips are not always viewed with certainty in determining age. However, certain generalizations can be made when labels and stamps are used in concert with the various techniques used by glassmakers.

Origin

The place of origin has been said to be the Boston and Sandwich Glass Works 1825-1888, Sandwich, Massachusetts. This is based on conjecture from many writers and personal observations of these figurals among Sandwich Glass collections of non-figural items. Researching Sandwich Glass has not revealed a definite connection. One can speculate that it may be Sandwich Glass based on the style and color of glass. There still is a degree of doubt and uncertainty that makes the use of the words “probably Sandwich Glass” by many writers appropriate.

Because of the diversity of figurals, in terms of varying styles and manufacture, they may have been produced by more than one glass company, other than in Sandwich. This seems to be especially true with the figurals toward the late 1800’s.

REACTIONS TO DESCRIPTIONS

In terms of an authentic representation of the Bunker Hill Monument, the figurals under consideration do offer the investigator a challenge. The basic problem lies in what we are able to accept as reasonable when a famous American landmark is or is not transformed into a bottle. The problem is unique when compared to other figurals. For example, Grants Tomb, the Statue of Liberty, and Eiffel Tower do not elicit the questions raised by this figural. Their identity is quite obvious when compared to original structures.

It is true, the designers of bottles use license in developing a bottle since function must be an important consideration. It must hold contents and needs to be handled so as to pour. This functional perspective usually necessitates a change in the appearance of the object it represents. In the preceding figurals the change was a cover as a bust of Grant that simply reinforced the Grant identity, the Statue of Liberty as a cover is much smaller in relation to the actual monument’s base, and the Eiffel Tower remains basically intact. There is not much question regarding what these figurals represent even as functional objects. It should be stated that most figural designers did make overall changes, but not to the extent of altering their identity.

The figurals cited in this article, is not an obvious representation of the Bunker Hill Monument. Yet, there are important clues that suggest some may represent this monument. As we probe, relevant descriptions of the bottles will be analyzed in an attempt to find out if the Bunker Hill Monument should be associated with all, none, or certain figurals.

Closure

It is not certain whether the designer of the glass stopper, in the form of an obelisk, used the monument as a model for this closure. It may have been simply developed out of an artistic rendering to give elegance to the bottle. The glass closure does pose the possibility that its maker viewed the bottle in relation to the monument. We are not certain, but it is plausible.

The cork closure does not detract from representing the monument. The designer used a neck, lip, and closure that were common in the 1800’s. The closure description keeps the door open for the possibility of a relationship with the structure in Charlestown.

Surface

The surface aspect brings us closer to getting a more substantial resemblance to the landmark. The stone work is not exactly like it in terms of the shape and number of stones laid in certain courses. In the monument the pattern of stones laid is basically in courses of three horizontal rectangular stones and five, including horizontals and squares. The undisputed similarity with the monument and bottle are the end square stones on every other course.

The low relief bottles more closely resemble the monument’s stone work. This bottle with its three horizontal rectangular stones on every other level, is also the same as the monument. Another close similarity is the courses above and below these three stones. In the bottle there is a uniform course of stones placed with two squares at each end and two rectangles in between. In the monument the squares are at the end, but in the middle is a square with a rectangle on each side. Like the bottle, the monument’s stone shapes change near the door and windows.

One can allow the designer of the bottle the right to change the shape and number of stones; to satisfy the particular needs of a smaller sized object. This is common in other figurals that depict structures containing irregular arrangements of stones.

On the monument the stones are laid with as relatively smooth surface. When viewed from a distance, for example from Boston’s Quincy Market, the stone work is not apparent. The obelisk resembles a solid form. This may be another reason why the figural’s surface treatment was not an important consideration for the designer.

The protruding stone work on the larger figurals and some of the smaller ones helps to grip the bottle. The smaller bottles with their stones not extended also makes sense; since a smaller bottle does not need the grip of a larger one. Function as a bottle is treated as more important than the object it may have represented.

Windows

The placement and number of windows and their appearance is of consequence in the answer to our question. It is here that a closeness to the Bunker Hill Monument becomes more apparent. The monument has four “square” windows, one on each side at the top just below the pyramidal section of the structure. They are not perfect squares since their sizes are two feet eight inches in height and two feet two inches in breadth. There are also seven rectangular windows up the north side, over the door.

In reference to the figurals, the most important likeness is in the four windows on their top and windows over door on most examples. The minor difference of top windows is their not being a square. However, in the smaller examples that have a smoother surface, the windows on the top four sides are less rectangular than the six above its door. Other examples have fewer windows above the door. Even though the actual monument has seven windows above the door making a total of eight on this side one should not quibble over the number of windows. This is mentioned since, as previously stated, figural designers as general practice changed the original object they were copying. The importance of windows lies in their presence and location, which are not found in other obelisk monuments.

The windows should be viewed as a momentous revelation in light of the fact that they isolate this figural, to a monument whose window arrangement was not common in the nineteenth century. Just as a matter of clarification, the much taller Washington Monument, 555 feet tall, has its sides of the pyramidal section of the structure. There are no widows on the four tapered sides.

Date

Until the emergence of the pontil example, Ca. 1841-1850, the date factor was not crucial. The dedication of the Bunker Hill Monument on July 17, 1842 does suggest the possibility of a commemorative bottle. Due to its scarcity, it was probably made for one or more dignitaries or at the whim of a glassmaker. We do not know. If it was a commemorative, this is not an uncommon occurrence with bottle. This ranges from flasks and inks to more recent Coca-Cola bottle. The importance of a date in this instance is that it signifies that the figural was not made before the dedication of the monument. This helps to pinpoint the figural’s date and that of the monument and offers a more substantial connection. It should be mentioned that the building of the monument was a long and drawn out task. The cornerstone was laid on June 17, 1825 and construction was begun in 1826. Construction and financial problems caused delays. With this problematic situation, an earlier date might have been acceptable for the bottle. It does not seem feasible that such a bottle could have been made until on or after the dedication.

The time frame of this figural covers a period of about sixty years. There may be a relationship with this and the appeal of the monument. As with other famous landmarks, this one also triggered related items like post cards, trade cards, a pickle bottle, cup plates, spoons, paperweights, tiles, and many other momentous. Whether one can compare the popularity of these objects and the production of the figural is possibly a clue to its life as a figural. One can simply guess at its possible transformation, from the monument so that persons could enjoy it as they used cologne or whatever other liquid it may have held.

Origin

The importance of origin is the bottle’s geographical semblance to the state in which the monument is located. This is based on the assumption that the bottle originated in the Boston and Sandwich Glass Works on Cape Cod in Sandwich, Massachusetts. The Proof is weak at this time.

The figurals that surface most often in Sandwich Glass collections are those that have the low relief stone and have the six windows above the door with the four square-like windows on the upper four sides. These appear to be the most like the actual monument and may reinforce the Massachusetts connection.

CONCLUSION: NAME OF FIGURAL

The evidence is certainly not as conclusive as other monument figurals that represent a particular namesake. Regarding these figurals, there are disclosures that makes one feel comfortable in concluding that certain examples could be the monument. As the article’s question was pondered, caution was consistently used in studying the monument and the different figurals. This mode of thinking is extremely important, since there can be the danger of getting caught up in the history and appeal of the monument and the often times, magnificent looking bottle. One does not want to cloud an answer with a judgment based on a fictitious account.

The research thus far has failed to reveal any documentation that specifically states that any of the figurals are representations of the monument. Studying the monument and different types of possible figural representations was helpful. The analysis made this writer feel secure in saying that certain figurals are depictions of the monument.

This conclusion is directed at those examples having the fine stone work with the six windows over the door and one on each side near the top. A second level of acceptance is the larger, bolder embossed figurals with the consistent four windows over the door and a window on each of four upper sides. The important fact about this figural is the inclusion of one window below each side of the pyramidal form. This is what makes it acceptable. With other types, one should use the words probably monument, or monument cologne.

CONCLUSION: FIGURAL AS AN ENTITY

In general, the figurals should be considered a highly collectible bottle. There are many variants, but as a grouping most are quite attractive, excite one’s historical curiosity, and exhibit an adequate level of quality in regard to the glassmaker’s production skills.

Upon closer examination, there is an aesthetic weakness in the missing pyramidal feature at the top of this figural. It takes away from the complete obelisk form that gives the viewer an uplifting and unifying feeling. The designer of the figural still deserves credit for developing a bottle that, in a limited manner, is good-looking. This is the case for those figurals that have a glass obelisk stopper. The glass stopper fills the void of not being completed on the upper portion of the bottle. Again, the surface treatment is an aesthetic remedy for others not having a glass stopper. On most examples it helps draw one’s attention away from the weakness on top through the stone work, windows, and doors. The stone work serves to give an overall interest through its varied patterns. The windows and doors assist in breaking the monotony that can arise from a repeated use of similar rectangular and square shapes. In contrast, the bolder embossed stones in some smaller examples that lack windows and doors are not as interesting. Their claim colorful and decorative labels.

The use of color provides compensation for many bottles, which lack or are weak in the other art elements of line, texture, and shape. Figurals are different in relation to other bottles. Their shape is a dominant feature and if properly executed by the bottle designer can in many instances overcome one’s reliance on color. Often times with figurals, color is the “frosting on the cake”. We can see that in the case of the bottle under discussion. Color becomes helpful since the over-all shape of the partial obelisk figural is not entirely successful without the surface variations previously men-illustrate how a figural can spark one’s curiosity abut history. It is not appropriate to discuss the history of the battle of Bunker Hill and its eventual monument in this article. This is something the reader can obtain from a host of resources. What is worth mentioning are the “go withs” that grew out of writing this article and cited in the previous discussion on the bottle’s date. This writer is collecting many of these objects not only because of a high interest in this monument, but to continue his search for unanswered questions. For example, a post card may reveal a message that provides important information not available in customary resources.

The workmanship of many of these figurals is not acceptable. As one studies the figurals from each of their four sides it is usually uniform. With certain types, the quality of workmanship is relatively consistent in terms of the sides tapering properly without being out of shape. The smooth surface examples in clear, color, and white milk glass are ordinarily properly formed. It changes when one views the bold stone examples; both smaller and larger versions. These range from being bent over as seen in the clear smaller examples. This may have been the basis for some opinions that they were earlier due to their crude manner of production. It seems that the degree of defective shaping is less apparent in the examples that had glass obelisk stoppers. Some may contemplate that this was because they were more recent. Others might theorize that they were made as decanters to be reused; due to their stoppers. This would be an interesting area to investigate; in searching out the age of the figurals and their use other than for cologne.

Today, many collectors accept poor workmanship as a characteristic of making an object unique, and not that of a mass-produced object. For example, the pontiled blue-purple bottle is not in perfect form as one views its four tapered sides. Yet, one might think because of its pontil and beautiful coloring it should have been made more carefully by the glassmaker. At this point, we just do not know what was going through the minds of the glassmakers in making certain types more perfect than others. Possibly, the protruding stone examples that tend to be less than perfect were older and as time passed, the glassmakers became better at blowing a four walled tapered shape. Of course, we should not forget that they were commercial ventures and were not directed at persons who would someday collect these bottles. It was previously stated that the blue pontil might have been a commemorative. In this situation, the commercialism factor would hold no weight. It is strongly felt that it was a matter of mastering a different type of form not common in the American glass works of the 1800’s.

VALUE SCALE:

Larger Size (Approximately 12″ in Height)

RANK DESCRIPTION EXAMPLE

1. Extrmely Rare blue-purple, pontil

2. Rare white milk glass with random splashes of color

3. Very Scarce cobalt, green, amber (with or without obelisk stopper)

4. Scarce white milk glass or opalescent with painted trim and obelisk stopper

5. Obtainable white milk glass

6. Common clear with obelisk stopper

7. Very Common clear

Smaller Size (Approximately 5″ to 10″ in Height)

RANK DESCRIPTION EXAMPLE

1. Rare cobalt

2. Very Scarce green, amythest

3. Scarce blue-green

4. Obtainable white milk glass

5. Common clear with label

6. Very Common clear

Bunker Hill Monument Cologne Bottle, (McK/Wil, plate 114, #3), (Barlow/Kaiser, plate 5199), American, ca. 1850 – 1870, deep amethyst color, 6 5/8”h, smooth base, sheared and tooled lip. A 97% original multicolored reads: ‘Cologne Water by D. Mitchell, New York’. The bottle is perfect. Bill Litle Collection. – Glass Works Auctions | Auction #128

“SKILTON. FOOTE & CO’S / TRADE MARK” / (Motif of Monument, Trees, and Pickle Barrels) / “BUNKER HILL PICKLES” (with 99% complete, original label), America, 1880 – 1895. Golden honey amber, cylindrical, tooled square collar – smooth base, ht. 8 1/8″, bottle is attic mint! Label has some staining, and is faded, but still legible, and reads in part, “MIXED PICKLES / FROM / SKILTON FOOTE & Co. / MANUFACTURERS / of / BUNKER HILL PICKLES”. A nice bottle, very scarce having the virtually complete, original label. – American Glass Gallery | Auction 15

“SKILTON. FOOTE & CO’S / TRADE MARK” / (Motif of Monument, Trees, and Pickle Barrels) / “BUNKER HILL PICKLES” (with 99% complete, original label), America, 1880 – 1895. Golden honey amber, cylindrical, tooled square collar – smooth base, ht. 8 1/8″, bottle is attic mint! Label has some staining, and is faded, but still legible, and reads in part, “MIXED PICKLES / FROM / SKILTON FOOTE & Co. / MANUFACTURERS / of / BUNKER HILL PICKLES”. A nice bottle, very scarce having the virtually complete, original label. – American Glass Gallery | Auction 15